I've been reading Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Ruefle lately. It's a beautiful book in the literal sense. A pristine eggshell white cover with the words Madness, Rack, and Honey in big script and the words spilling over the sides. Typeset in a beautiful serif font, it gives the light impression of a writer while shedding the normally intimidating air of literary books for a playful whimsy.

When anyone asks me what I've been reading lately, I pay special attention to how people react as I read off the title. There's an air of mystery that provokes curiosity. All known words, simply set in a list and bunched together, and that is enough to seduce many. The name itself takes up so much space, too. It's a long title, and its weight lingers in the air when it's spoken. I tell people it's a book about poetry. I tell people it's one of the better ones.

Ruefle starts off the book by saying that "all she has to say about poetry" is:

"I don't think I really have anything to say about poetry other than remarking that it is a wandering little drift of unidentified sound, and trying to say more reminds me of following the sound of a thrush into the woods on a summer's eve - if you persist in following the thrush it will only recede deeper and deeper into the woods; you will never actually see the thrush (the hermit thrush is especially shy), but I suppose listening is a kind of knowledge, or as close as one can come."

I want to learn how to listen. I hope this book shows me some sliver of how.

In the titular chapter, Ruefle explains the title and the meaning behind each word. Honey is the burst of joy the moment the words flow just right, when it seems like there is a container, if only for a moment, that captures the exact immensity of what you feel. And then that moment is gone, and the flies are swarming, and you're deep in the rack of it, that torturous teetering between those moments of indelible satisfaction and those of frantically searching for the lost feeling.

As poets1, we are junkies addicted to capturing feeling (an act of equal parts intellect and emotion). Our duty to ourselves is to commit to this unending cycle of suffering—to find heaven and exile ourselves in search of another.

We cannot help ourselves. We are obsessed with the absurdity of it all. And that is the madness of it. We cannot help but dedicate ourselves again and again to the practice of living, expressing, feeling—over and over and over again. We are seeking to be the most human we can be.

Henrick Karlsson and Johanna Wiberg recently wrote about where good ideas come from. By studying the working notebooks of two creative masterminds, mathematician Alexander Grothendieck and film director Ingmar Bergman, Karlsson and Wiberg excavate the theory that good ideas need to come from solitude, where you learn "what personal curiosity feels like in its undiluted form."

One of the biggest differentiators they identify is the ability to linger in the confusion of their thoughts. They are curious about their confusion, and as a result, they form the environment that allows for new questions to emerge, a skill far rarer than the ability to answer questions. This ability to sit at the "margin of society," as they call it, is what creates the opportunity to come up with new, transformative ideas.

But there's a danger here that is left unsaid. If you linger too long in this liminal space, you can become lost in your own world, largely cut off from society. Many infamous extremists had the same notions of greatness and being on the edge of something new and transformative as these creative masterminds2. To bring great ideas to life, you have to balance yourself in this constant tension, simultaneously fighting the void of your mind and the pressure to conform to society.

This is the madness that Grothendieck and Bergman undergo in their creative practices. They must constantly push against their own boundaries of expression, breaking through just to find it pop up somewhere new to repeat the process all over again.

Why does life have so much suffering? is a question that makes regular visits to my mind. I think about dialectics, "the self-consciousness of the objective context of delusion." Dialectics is a fancy way to refer to the madness of living and enjoying the simplest things in a fucked up world.

The other day I was talking with a mother about the conversations she has with her children when they ask about why they have to do active shooter drillers in Texas. We were walking through downtown Seattle by the water on a beautiful summer day, the sun casting each passerby in an angelic glow. The juxtaposition was terrifying and comforting.

I don't know the answer to the question. I couldn't give a satisfactory one in writing if I tried. But I sometimes see glances at an answer. Often in poems. Sometimes I even write something that feels like my answer, although usually its lifespan is short-lived, and I'm back sitting with the immensity of the question again. But for that time when everything feels like it fits together nicely—boy, does that feel good.

I've been thinking about what it means to practice poetry, and I think the best answer I can come up with is that it means practicing living.

I sometimes wonder how the best poets of our era spend their days. I imagine Ocean Vuong washing dishes as if it's the only thing in the universe, appreciating those singular honeyed moments before the inevitable lilt into rack and existential awareness of the madness that Ruefle speaks of. I picture how Mary Oliver starts her morning. What does she do while she waits for her coffee to brew? How many birds does she bid good morning to?

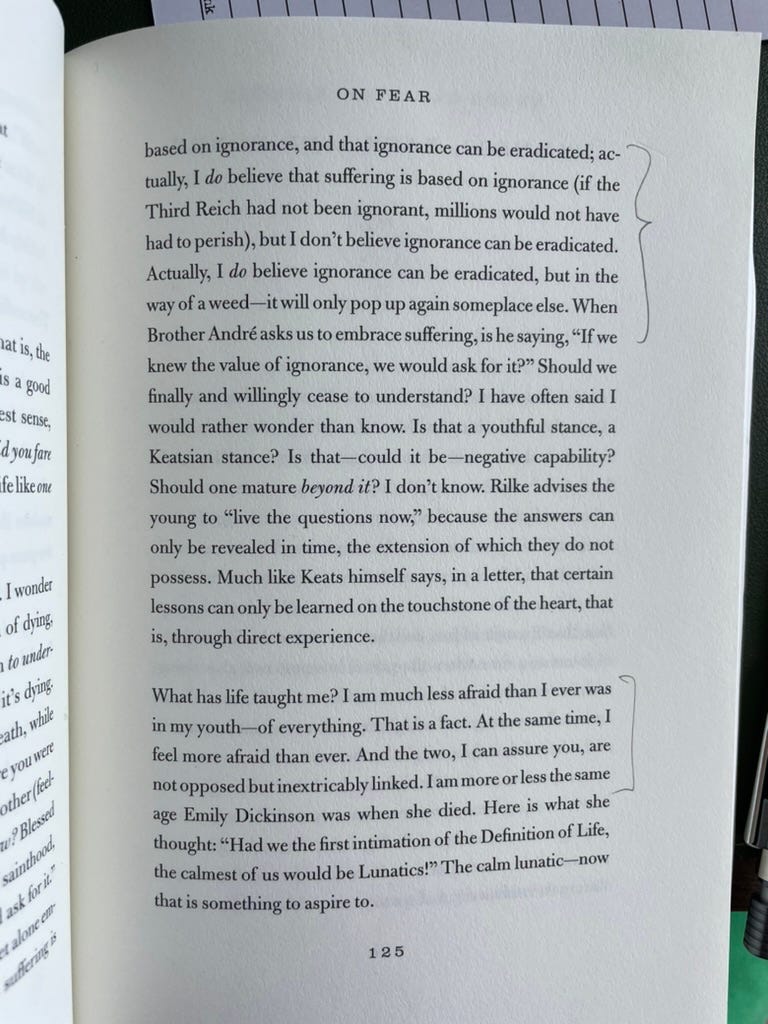

I think this is what Ruefle means when she mentions "the calm lunatic." We must simultaneously hold the world's contradictions—all the meaningless suffering and hate in the world with all the simple joys and rights that we take for granted. We can be less afraid of everything that we feared when we were young and more fearful than ever. We can doubt that anything happy will last, and we can believe that people are fundamentally good at heart. We can hold it all in our hearts, if we train to be strong enough to bear it.

I imagine these poets practice listening to what life is saying, the scattered bits of sound that emit from the upswell of everyday activity. Their poems are collected collages of these scraps of sound.

I am trying to listen. I am trying to live. I am taking a deep breath, now. I am going to sit with the madness for a moment longer.

How did you feel when I referred to all of us as poets? Did you feel nervous, did you push back on it, a bit angry, even? I think everyone has the capacity to be a poet. We weave poetry in the simplest moments of our life. So if that identifier felt threatening or inappropriate in any way, I encourage you to try it on for a spin for the rest of this article. What would the poet you do? How would they read? What does that drift of sound remind you of?

Ted Kaczynski also had radical, transformative ideas.

living as practicing poetry ❣️ I've been feeling that a lot lately, in the opposite. Using art (dance, writing) as a way to practice life

Love every moment of this. Thank you!